BUT I did spend three years at the HSC Wing (80 H-60s and 3000 personnel) Safety Officer in San Diego and took to heart the importance of safety programs during my tour there. It's appropriate that the genesis for my article--a Military Times article this week titled "The death toll for rising aviation accidents: 133 troops killed in five years," included a photo collage of those who've lost their lives this past year because all too often the human cost can get lost in the sterile analysis of flight hours and numbers. These aviators and aircrew had spouses and children and loved ones who carry on with a hole in their hearts and lives that will never be filled.

During my tour as the Wing Safety Officer I had the heart-breaking task of investigating a class-A mishap for my former squadron. I was woken with a call from our Commodore one night telling me that a helicopter had crashed. My throat caught immediately and then my heart crashed when he told me it was my old squadron. He asked me to meet with the search and rescue boat at the Coast Guard station and I quickly put on my uniform and drive from my home in Coronado to the Coast Guard station downtown. I was there when they unloaded the remains and personal items they had recovered. To this day I can't smell JP-5 without being taken back to the pier there. In the early hours of that morning, I had the somber honor of escorting the bodies of my colleagues in the ambulance to the morgue at Balboa Hospital. I didn't want them to be alone in this journey and I thought it important that they be accompanied by someone who knew their face, their smile, their laughter.

I share these details to underscore that there's not an aviator out there who doesn't hear about an aircraft crashing and immediately stop and hope and pray that it's not someone they know.

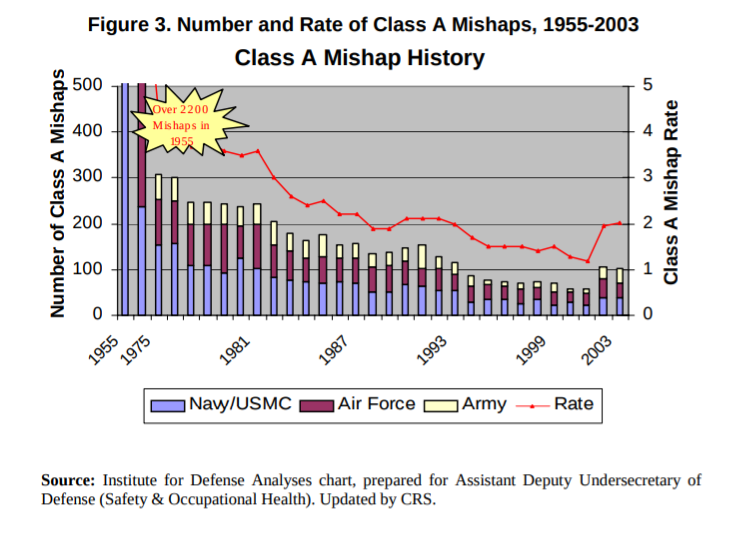

And I'd venture to guess that there's very few of us who haven't been to at least one funeral or service during our careers. Aviation safety is something that should be important and personal to everyone in our field. We owe it to one another to take it seriously and with the gravity it deserves. Aviation safety has come a long way since the pre-NATOPS, pre-Safety Center pioneering days and to its credit, mishaps have plunged since the 1950s. While today our Naval Safety Center today takes its job seriously, aviation safety can't happen at the headquarters level. Aviation safety starts with the individual.

Me.

You.

It was one of these individuals that saved my life during a series of unaided night landings on a small boy during my fleet tour. Not yet an aircraft commander and on approach and at the controls during a near zero-illum night, I experienced vertigo and thought I was coming over the ship's deck when I was actually several hundred feet short. Had not AW2 Baecker, one of my aircrewmen in the back, not felt the ocean spray at under ten feet coming into the cabin and screamed for POWER, POWER, POWER, I would have been one of those faces in a collage. Had it not been for her, I wouldn't never have met my wife, never had 5 beautiful children to come home to every day. My entire future and that of my crew, would have vanished at the bottom of the ocean. Were it not for AW2 Baecker, I would have flown the helicopter right into the blackened sea.

Building an enterprise-wide safety culture is a deadly serious endeavor.

I've never shared all of these things publicly but I do now because I believe that it's important that articles like this are shared and discussed because a safety culture doesn't exist in a vacuum and productive, robust safety cultures don't happen by accident. When possible trends are identified, it's important to dig deeper and work to improve across our services. In keeping with this spirit I'd say this article is a worthy starting point if you want to analyze possible systematic safety issues within DoD aviation. The article focuses on the role of diminished flight hours which I believe could play a part in the rise in mishaps but I'd also point out that the "swiss-cheese" nature of aviation mishaps means that even wider trends seldom come down to one simple root cause (and with increasingly sophisticated aircraft and peripheral equipment, just scratching some paint can give push you into the Class C threshold). Unfortunately, in some cases, despite rigorous and exhaustive analysis and investigation, we never know exactly why a mishap occurred.

Following is a brief (admittedly Navy-centric) summary of items that our service safety centers could coordinate on in their analyses.

1. HAZREPS (Hazard Reports) and equivalent reporting across the services (and sharing of information).

2. Service-variable attrition standards throughout flight school. Put simply, how many downs before you fail out? How has this changed over the years? An OVERLY simplified explanation is that these standards tend to change over the years driven by service manning requirements.

3. Human Factors. The majority of aviation mishaps come down to this at some point in the chain of events. This is where one might find useful trends. I don't believe services are sharing this information in a central repository at this time.

4. Squadron safety culture. While "safety culture" is a nebulous terms, there are methods to at least begin to quantify this:

- Are squadrons getting the baseline surveys done (e.g., CSA, MCAS, NSC surveys, Safety Standowns, Human Factors Councils, Enlisted Safety Committee meetings, anymouse submissions) on a regular basis?

- Are Commanding Officers debriefing and addressing any noted issues in a timely and transparent nature?

- Are squadrons maximizing simulator use when flight hours are reduced?

- Are squadron writing safety articles, submitting NATOPS changes, making NAMDRP/JDRS submissions?

- Are squadrons ensuring all required ORM coursework is complete?

NOTE: here's some good background on safety culture here: http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a490843.pdf

5. More rigorous and systematic Class C analysis is necessary to determine if their rise are actually "lagging indicators" of wider problems or not.

6. Intra-service best practices. This is likely an area where the services can improve. Yes, each service has specific cultures, missions, and standards that make quantitative analysis difficult but that doesn't mean we shouldn't strive for this. For example as a starting point:

- Do services share best safety practices?

- Is there a method to share this type of information?

- Does one service have a better method for the equivalent of NATOPS checks?

This is an admittedly difficult goal because it requires a level of trust between services and requires a willingness to highlight shortcomings and failures.

Further references:

2003 CRS Report on Military Aviation Safety: https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20031125_RL31571_1e95b1b93a0fcdee4874121b47fa34a65fcc4c04.pdf

No comments:

Post a Comment