Notes on "Making Remittances Work" by Gupta et al

BONUS LINK: My entire (so far) grad school notes collection can be found here.

Formal remittances in Africa pale in comparison to the rest

of the world. African remittances make

up only 4% of the global total. From

2000-5 they have increased by only 55% while the rest of the developing world’s

remittance levels grew 81%. On average

remittances account for only 2.5% of the GDP for African states versus 5% for

developing states in other regions (i.e. East Asia and Latin America). This numbers are somewhat skewed by the

informal African remittance market (e.g., hawala

system). The remittance black markets

account for 45-65 % of all money transferred back to Africa.

While these

remittances have made a difference in combatting poverty in Africa, it must

first be noted that they are no substitute for sound, long-term economic

development policies. Furthermore,

governments must be aware of the remittance levels lest they become victims of

Dutch disease and RER appreciation. It

is clear, however, the remittances to augment household income and increase the

level of sustenance families are able to provide. Villages see the benefits of these

remittances and will pool their resources to send their brightest youths abroad

(or to the city) to earn a degree so that they can utilize this income

stream. While the research attempting to

show a direct causative relationship between remittances and poverty reduction

have opaque, Gupta does note that with a remittances to GDP ratio rise of 10%,

one garners a reduction of 1% in people living on less than $1 a day.

Other

benefits that remittances bestow on African economies include long-term

economic growth potential. Remittances

allow many Africans to open savings accounts for the first time. These actions lead to investment

opportunities for entrepreneurs in the African states. Furthermore, the remittances often serve as a

stabilizing factor against international fluctuations in aid as well as global

economic meltdowns. The tendency for

villages to send pupils abroad may contribute to a brain drain (at least

partially), however, everyone doesn’t leave and there is corresponding evidence

(especially in the health care industry) that remittances has increased the

number of qualified health care providers in many African states.

Despite

these positive factors there is much that can be improved for remittances in

Africa. First the switch must be made

from the informal markets like hawala

to formal markets. Namely this

requirement will drive down risk for those transferring money. An increase in formal markets providers must

coincide with less taxes and fees for those remitting money. These high taxes are the underlying cause the

drives individuals to use informal systems.

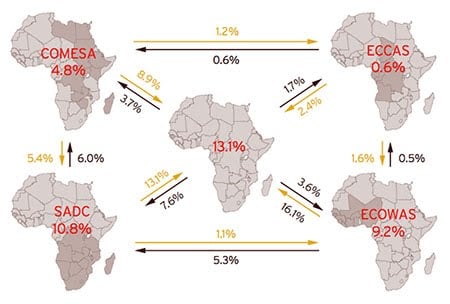

Regionalization must also be promoted; this will allow regulation across

the borders of neighboring countries so that uniform policies can be understood

and use. All of this must drive

innovation—remittances are an ideal avenue by which to reach the unbanked. In a novel effort, US banks set up a deal for

remittances with people in Cape Verde that was very successful. Some remittance credit union networks have

been set up in southern African—these networks don’t require those receiving

the money to have an account at the bank—making remittance reception easy and

attractive. Banks and MTOs must create

ways to bundle services—this means that one could transfer money back to their

home state but also investment and get loans.

On the subject of loans, in other developing regions, remittances have

successfully been used as collateral for larger loans. This has led to huge growth in the housing

market in Mexico for instance. For such

growth to occur in Africa, however, remittances will have to grow well beyond

their paltry 4% market share. Finally,

cell phone technology is already been used to allow people to bank via their

phone. The incorporation of this

technology will prove crucial to the future of remittance.

Rough Notes:

Remittances Compared:

-

2000-5 increased 55% to $7 billion (compared to 81% globally)

-

only 4% of total remittances

-

Nigeria the only country in the top 25 globally

-

smaller relative to GDP as well (2.5% versus the 5% in other developing countries)

EXCEPT: Lesotho, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau and Senegal

-

Higher percentage in Africa flow through

informal channel though (45-65%) and exclude intraregional remittances (strong

in southern Africa)

Remittances' Impact:

-

FIRST: no substitute for sustained domestically engineered development

effort/strategy

-

SECOND: stay alert to Dutch disease and RER appreciation

- Augment

households resources, smooth consumption, provide working capital,

multiplicative effects on household spending

-

finance consumption, invest in education, health care, nutrition

-

Villages pool resources to send smartest abroad—so higher poverty might mean

more remittances

-

Remittances to GDP ratio rise (10%) = 1% less people living on less than $1 a

day

Remittance benefits:

- Long

Term Growth Potential- depends on how they are used. If they are used in concert with investment

channels they stimulate growth

-

Financial Development –enable access to financial markets for those previously

unable starting with savings products.

Possibility to use them as collateral with microfinance projects. This is financial deepening.

- they

can be a stabilizer against fluctuations in Aid and FDI

-

possible increases in health care workers

Remittance Future:

- Less

taxation and fees. Cost of small sums is

very high. This is due to low volume and

lack of form institutions capable of carrying out the transfer

- right

now many depend on the hawala system (east Africa)—but these carry significant

risk

-

no major MTO like wester union in south Africa.

9/11 has made it even harder to own or start an MTO

-

financial sector reform—permitting citizens to open foreign currency accounts

-

cross border fee regulation and uniformity

-

connect the unbanked population (US Banks doing this with Cape Verde)

-

adapt to migrant need—International Remittance Network (200 credit unions)

doesn’t require recipients to have a bank account.

-

Cell phone technology allows money sent as text message—cell phone

banking—linked to debit cards

-

Channel savings to productivity (beyond savings) like human capital development

through housing construction and financing—these require greater financial

infrastructure though than many African states have

-

SSA banks need to bundle services (savings products and entrepreneurial loans)

to remittance families –something not done by Western Union