In the spring and summer of 1994, I was 15 years old and a freshman at Bedford High School in Massachusetts. Searching my memory of that period, I can't recall even a quick polaroid recollection concerning almost a million people's murder.

That spring

I remember working as a bagger at the grocery store on Hanscomb Air Force Base.

I remember fleeing the base theatre with my friend CJ after we lit up cigars during a movie.

I remember the field where I would play soccer by my school.

What I can recall

I close my eyes and I can smell the dusty paper of the grocery bags.

I close my eyes and I can feel my heart racing as we were chased out of the theatre.

I close my eyes and I can see the long and overgrown green grass of the soccer field.

That same spring

Nearly a million people's last breath and smell was rotten and rife with sweat, urine, and blood.

Murderers crushed and ripped apart nearly a million hearts.

Murderers smashed shut nearly a million sets of eyes.

That same spring

Millions of people

knew.

And millions of people did

Nothing.

Today

Today

Today

Today

and everyday

I trudge with the grief of my own ignorance like a iron yoke on the shoulders of my soul.

The Guilt of the Silent: An Analysis of Raoul Peck's Sometimes in April

In 2004’s Sometimes in April, director Raoul Peck creates a graphically accurate

account of the genocide that began after Hutu extremists and members of the

Presidential Guard shot down a plane carrying Rwandan President Habyarimana and

Burundian President Ntaryimira on 6 April 1994. This event ignited a killing spree that spread from Kigali

throughout the country, claiming the lives of over 800,000 people—507,000 of

them Tutsis (77% of registered Tutsi population), [i]

in the span of 100 days. [ii] While the film’s details of these 100

days reflect years of careful research by the director, Peck neglects several

key elements whose inclusion would strengthen his story’s purpose. From the start, the movie falls short

in offering deeper context to the relationship between the Hutus and Tutsis

throughout Rwanda’s history. While

the film captures the inaction of the international community throughout the

genocide well, the director’s decision to ignore the negligence and lethargy of

specific individuals and administrations is a disservice to all those

killed. Lastly, the film fails to

address the significance of current Rwandan President Paul Kagame’s decision to

initiate countrywide gacaca

“grass courts” in 2001 in the midst of continuing deliberations by the

International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR).

There

is little to criticize, however, in the Peck’s portrayal of the events

occurring in Rwanda during the genocide.

The movie’s action hinges on the relationship between fictional

characters Augustin, a moderate Hutu captain in the Rwandan military (married

to Jeanne, a Tutsi), and his brother Honoré, a popular “Hutu Power” radio DJ

for Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM). During the genocide, the international community protests

RTLM as “hate” radio; its DJs regularly list the names and addresses of Tutsis

and moderate Hutus so they can be targeted and killed. As violence erupts, Augustin fears for

his life and that of his family.

After much pleading, he convinces his brother to take his family to the

Hotel Mille Collines where they will be safe, deciding that his brother’s

reputation gives them the best chance to make it through the deadly roadblocks

in the capital city Kigali. After

successfully negotiating a few roadblocks run by civilian militia, Honoré comes

to one run by the military that he is unable to pass or bribe his way

through. Helpless to intervene, he

watches in anguish as Rwandan military soldiers murder his brother’s

family. Honoré sneaks back to the

pit under the cover of night—miraculously finds Jeanne alive, and carries her

to a local church. Jeanne survives

and is later taken by Rwandan soldiers and gang-raped repeatedly. In a fitting piece of justice (one

based on real events), she grabs a soldier’s grenade and kills herself and a

group of them after a brutal rape session, to include a complicit priest (also

based on real events).[iii] This narrative draws to a close as the

Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), led by General Paul Kagame, defeats the Rwanda

military and militias, restores order and brings the genocide to an end. The other story told by the film, in

parallel, focuses on Honoré’s trial at the ICTR ten years later, and the two

brothers’ reconciliation. The

director uses their rapprochement to illustrate the complex nature of Rwanda’s

post-genocide growth and progress toward normalcy.

The

film itself begins by tracing the onset of ethnic conflict in Rwanda from the

post-World War II handover of colonial control from Germany to Belgium, noting

that for centuries Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa “shared the same culture, language and

religion.”[iv]

While it is true that they all shared a common language, Kinyarwanda, whether

all three are part of the same ethnic group is a matter widely debated by

scholars.[v] Furthermore, this opening statement

paints too rosy a picture, as it fails to acknowledge the Tutsi’s marked

centuries-long subjugation of the Hutus.

While these details do not excuse the genocide, including them would

offer insight into the psyche of the Hutus and the way in which it was

manipulated, ultimately leading to decades of horrific violence. The disagreement among scholars centers

on the argument that a better description of the Hutus and Tutsis is be one of

different ethnic groups living in the same society as part of a feudal or caste

system.[vi] Regardless of the debate, what is clear

is that they lived in the same region among each other for more than a thousand

years. As different groups

(belonging to different families and following different leaders) settled into

the area, the cattle-herding pastoralists (the Tutsi people) consolidated power

and militarily established a rule (under mwamis, or kings)[vii] over the

region, creating an elite class that would evolve over the centuries. Not every cattle-herder was part of the

ruling class, however, and some farmers (Hutus) also rose to prominence

(especially those skilled in battle).[viii] In general, a Hutu could become a Tutsi

if he bought enough cattle to elevate his social position. Although even if a Tutsi lost all of

his cattle, he would not then become a Hutu. So until the 1800’s, the terms Hutu and Tutsi retained a

degree of fluidity, and people were more apt to define themselves by a specific

region or lineage than by the term Hutu or Tutsi.[ix] It was at the end of the 19th

century, as society in Rwanda became more developed and complex that a degree

of rigidity emerged in how the ruling class defined itself. The Tutsi ruling

class came to define themselves by their power and wealth (typically measured

by the number of cattle owned). The masses and peasants did not own cattle and

were thus defined as subjects, or Hutus.[x] It is worthwhile to note, that while

historians typically recount the relationship between ruler and ruled with a

degree of ambivalence, conquest and violence was an essential part of it. In the next century for instance, Hutus

would call for a ban on the Kalinga,

the royal Tutsi drum decorated with the testicles of defeated Hutu princes.[xi]

It

is then unfortunate that this consolidation and modernization by the ruling

class coincided with European conquest.

In an effort to maintain control and maximize economic benefit, the

Belgians torqued the system already in place, choosing to conduct official

communication only with the ruling class, this belief stemming from their own

warped ideas about racial superiority.[xii] This interaction carried over to the

religious side as well until the 1930’s when Flemish priests replaced Belgian

Catholic ones. These typically

poor Flemish priests more closely related to the Hutus economically. So while educational

opportunities came, they were the second tier ones available through the

Catholic church. In contrast,

Tutsis received the superior French education available through the Belgian

government.[xiii] It is at this point that the film

describes well the racial classification system put in place by Belgium, one

that included identity cards that listed the bearer as “Hutu” or “Tutsi.” In removing any chance for upward

mobility among those ruled (Hutus), the Belgians fostered a growing resentment

that would fester for several decades.[xiv]

This

bitterness manifested itself in 1959, when Belgium rule ended, and power was

turned over to majority rule. On

28 January 1961, the majority (Hutus) spoke and deposed Tutsi King Kigeli V,

replacing him with Hutu president Grégoire Kayibanda.[xv]

Over the next several decades, hundreds of thousands of Tutsi would flee the

country; by 1994 it was estimated that there were between 400-700 thousand

Rwandan Tutsis living outside the country.[xvi] It is this long history that one finds

the fuel for the fire that became the

genocide.

It

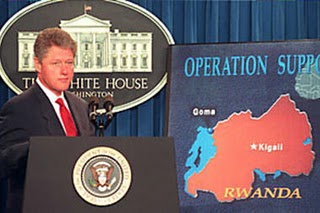

is in his description of the international response to this fire that Peck falls short. The film’s primary focus for this is through the actions of

Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Prudence Bushnell, and

through her efforts to influence the United States to act to intervene. True to the historical record, she is

roundly rebuffed by the administration above her when she tries to motivate

action. The film never names

those squelching her effort, however; nor does it delve into the specific

details of President Clinton’s blind eye.

These details are important because they offer insight into the U.S.

decision-making process and the efficacy of the United Nations. A day after the president’s plane

is shot down, the film shows Bushnell referring to a 9-week-old CIA report that

warned of the potential for widespread violence. Bushnell is reprimanded by an older white gentlemen (one

assumes this to be Secretary of State Warren Christopher) “not to bring up the

CIA report again.”[xvii] The pacing of the film’s cuts to the

inaction in Washington exacerbates the lack of detail. In offering only infrequent cuts, Peck

fails to tell the viewer the scene’s place in the genocide’s timeline. Thus when the films shows an internal

USG debate via teleconference regarding the possibility of jamming the hate radio stations (a measure deemed “too expensive and illegal”)[xviii],

the viewer doesn’t know that this debate occurred on or about 5 May, nearly a

month after the killings (roughly 200,000 dead)[xix]

began.[xx] Other than a few news clips of State

Department officials playing semantics with the term genocide on Day 65 of the

crisis (620,000 killed),[xxi]

and a final shot of a nameless White House official thanking Bushnell for her

team’s work on the U.S. belated humanitarian response (which actually aided the

escape of many of the murderers), no other evidence of America’s action is

investigated.

This

omission is unfortunate because there are hundreds of previously classified

documents (all available at the time of the filming) that make it clear that

the U.S. was aware of the slaughter and murder of civilians at the highest

levels, and not only did nothing, but in some cases made efforts to ensure

others did nothing as well. Partly

in response to a request from the Belgian government for “cover’ in their

withdrawal[xxii], on 15

April (64,000 dead)[xxiii]

Christopher sent a cable to the U.S. Mission to the United Nations. In it he stated the U.S. position that

the United Nations Assistance Mission in Rwanda (UNAMIR) must be withdrawn, an

imperative that would be echoed during a Security Council meeting at which the

Rwandan ambassador was present and able to communicate the information back to

the genocide’s perpetrators.[xxiv] The Clinton administration, through

National Security Advisor Anthony Lake, continued to receive intelligence

reports on the killing to include a 26 April one stating that at least 100,000

had been killed.[xxv] Perhaps most damning, however, is a 21

April letter from Rwandan human rights activist Monique Mujawamariya to

President Clinton; in the letter she writes of the genocide occurring and the

dire effect that a UNAMIR drawdown would have.[xxvi] Clinton had met Mujawamariya the

previous year and when she went missing in Rwanda in early April, finding her

became a central task for his staff.[xxvii] After she managed to escape Rwanda and

was found, however, her pleas—and her letter, went ignored by the White

House. At the United Nations, the

U.S. continued to stymie efforts to intervene. In a 28 April memo to Madeline Albright from Deputy Political

councilor to the UN John Boardman, he cautions her to remain “mostly in

listening mode… not commit [the] USG to anything.”[xxviii] Early wording in the same memo makes it

clear that the U.S. was aware of “atrocities” being committed in Rwanda. The ambivalence and impotence of the

White House is best shown in that Rwandan assets in the U.S. were not frozen,

and diplomatic relations with the genocidal government were not cut off until

15 July, 11 days after the genocide’s end.[xxix] During the films final seconds, the

words, “Of those who watched the genocide unfold and did nothing to stop it, no

one has been charged” appear on the screen. By using these documents, and

countless others available, Peck could have made clear exactly who those who

watched the genocide unfold were.

Finally,

the film shows both the ICTR, as well as the gacaca courts taking place in the countryside villages

where the genocide occurred. The

gacaca courts were instituted to address

the backlog of 110,000 alleged genocide perpetrators in 2001.[xxx] Widely criticized by human rights

activists, the informal courts (led by ‘judges’ with only a modicum of legal

training) were held in the villages where the crimes occurred, and allowed

victims to confront their attackers directly. Peck fails to show these controversies, however; nor does he

show that in some cases the criminal’s confession itself was his only

punishment (in many cases it was a combination of confession and time served).[xxxi] While the competing ideas of

retribution and justice in post-genocide Rwanda may have been too large a

project to address in an already long (2 hour and 15 minutes) film, the

director could have made clear that the gacaca courts were a deliberate effort by Tutsi President

Kagame to help rebuild a sense of normalcy and an ability for Rwanda to move

forward.[xxxii] In one of the most densely populated

countries in Africa,[xxxiii]

it was clear that Hutus and Tutsi would have to live amongst each other as

their country recovered.

Given

an event as large and complex as the genocide in Rwanda, Peck does an admirable

job in addressing the ways in which the extremist elements of the Hutu military

and political militias took advantage of the Tutsis’ past systemic subjugation

of Hutus. The pervasive power of

this propaganda is well illustrated in the character of hate radio DJ

Honoré. As Peck superbly

captures the graphic and explicit imagery of genocide, he is in his element,

creating scenes that cannot be ignored, nor ever forgotten by the viewer. Thus it is all the more unfortunate

that the film’s beginning words by Martin Luther King Jr., “In the end, we will

remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends”[xxxiv]

are not fully honored by naming those silent offenders in the United

States. Perhaps by holding these

mute transgressors accountable, future atrocities can be prevented.

Notes

[i.]. Alison

Liebhafsky Des Forges, Leave None to Tell the Story: Genocide in Rwanda, (New York: Human Rights Watch, 1999), 15.

[ii]. Frontline: Ghosts of Rwanda,

“Timeline,” last modified April 1, 2004, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/ghosts/etc/crontext.html.

[iii]. Sometimes in April, “Director’s Commentary,” directed by Raoul Peck

(2004; HBO Home Video, 2005), DVD.

[vi.].

Paul Nugent, Africa Since Independence: A Comparative History, (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), 51, 499.

[vii]. Wayne Madsen, Genocide and Covert

Operations in Africa, 1993-1999, (Lewiston,

NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 1999), 100.

[xi]. Madsen, Genocide and Covert

Operations, 101.

[xii]. Ibid., 100.

[xiii]. Ibid., 101.

[xiv]. Sometimes in April, Peck.

[xv]. Madsen, Genocide and Covert

Operations, 103.

[xvii]. Sometimes in April, Peck, 41:08.

[xviii]. Ibid., 1:18.

[xix]. Frontline, “Timeline.”

[xx]. Frank G. Wisner, “DoD Memo, Rwanda:

Jamming Civilian Radio Broadcasts,”

The National Security Archive, The Genocide and the US in Rwanda, edited

by William Ferroggiaro, last modified August 20, 2001, http://www.gwu

.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB53/rw050594.pdf.

[xxi]. Sometimes in April, Peck, 1:38.

[xxii]. Samantha Powers, “Bystanders to

Genocide,” Atlantic Monthly, September

2001, http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/print/2001/09/bystanders-to-genocide/4571.

[xxiv]. Warren Christopher, “Talking Points on

the UNAMIR Withdrawal,” The National Security Archive, The Genocide and the US

in Rwanda, edited by William Ferroggiaro, last modified August 20, 2001,

http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv

/NSAEBB/NSAEBB53/rw041594.pdf.

[xxv]. Bureau of Intelligence and Research

Report: “Rwanda: Genocide and Partition,” The National Security Archive, The US

and the Genocide and Rwanda, edited by William Ferroggiaro, last modified March

24, 2004, http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv

/NSAEBB/NSAEBB117/Rw23.pdf.

[xxvi].

Monique Mujawamariya, letter to President Clinton, April 21, 1994, The National

Security Archive, The US and the Genocide and Rwanda, edited by William

Ferroggiaro, last modified March 24, 2004, http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv

/NSAEBB/NSAEBB117/RW47.pdf.

[xxvii]. Powers, “Bystanders to Genocide,” VII.

[xxviii]. John S. Boardman, United Nations Memo

to Ambassador Albright, April 28, 1994, The National Security Archive, The US

and the Genocide and Rwanda, edited by William Ferroggiaro, last modified March

24, 2004, http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv

/NSAEBB/NSAEBB117/Rw12.pdf.

[xxix]. Jared Cohen, One Hundred Days of

Silence: American and the Rwanda Genocide,

(Lanham: Rowman and Littlefied, 2007), 148.

[xxx]. Nugent, Africa Since, 484.

[xxxi].

Philip Gourevitch, “The Life After: A Reporter at Large,” The New Yorker, May 4, 2009, http://search.proquest.com.libproxy.nps.edu/docview/233155205

/fulltext/134F41AF92127BBFB2B/1?accountid=12702.

[xxxii].

Gourevitch, “The Life After.”

[xxxiii].

Des Forges, Leave None, 31.

[xxxiv].

Sometimes in April, Peck.

http://fuuo.blogspot.com/2012/02/sometimes-in-april-analysis-paper.html

http://fuuo.blogspot.com/2012/02/sometimes-in-april-analysis-paper.html

No comments:

Post a Comment